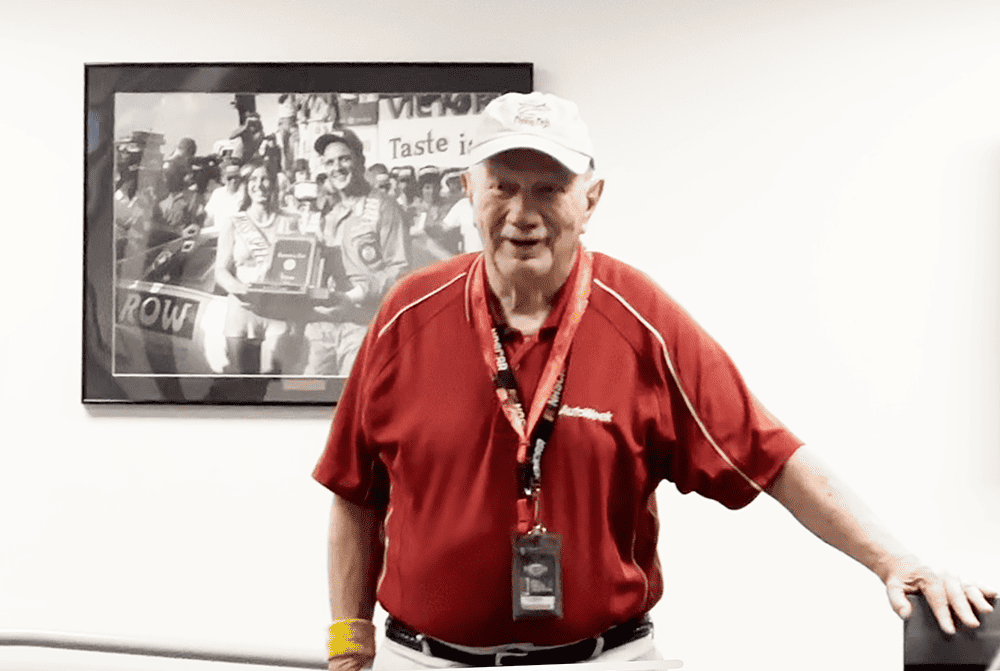

By All Pearce, Special Guest Writer

It was early June of 1976, and Americans were preparing to celebrate their country’s 200th birthday. In less than a month, on July 4, millions from coast-to-coast would mark the 1776 anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and the beginning of the American Revolution that brought hard-won independence from Great Britain.

In northwestern France, officials were wrapping up preparations for their 44th annual 24 Hours of Le Mans around the 8.467-mile Circuit de la Sarthe. In honor of America’s bicentennial, the Automobile Club de L’Ouest had invited two NASCAR teams to bring stock cars to the world’s most prestigious sports car race the weekend of June 12-13.

And in eastern Virginia, a couple of newspapermen were finalizing plans to be there. Randy Hallman of the Richmond News-Leader and Al Pearce of the Newport News Times-Herald had been covering NASCAR for years. They often traveled together and reported from such far-flung venues as Daytona Beach, Talladega, Dover, Martinsville, and Darlington. They were crossing the pond primarily to write about the American teams of owner Junie Donlavey and owner/driver Hershel McGriff.

“I’m not sure we knew what we were getting into,” Pearce recalls of that long-ago road trip of all road trips. “Randy was more into international racing than I was, and both of us were more accustomed to weekend short-track races. It was going to be a ‘great adventure’ in almost every sense of the word, so we were pretty excited. Maybe a little anxious about parts of the trip, but we figured we’d muddle our way through, one way or another.”

The long-time colleagues were basically on their own. Their newspapers offered some financial help, but hardly enough to break even. For Le Mans, they rode together from Richmond to Newark, flew low-cost Icelandic Airlines to Luxembourg, then took an overnight train down to Paris.

They found a small, affordable hotel and spent a free day in Paris. On Thursday, Pearce went to Stade Roland Garros to watch the French Open tennis tournament. Hallman went sightseeing, and to visit an automobile dealership where the legendary motorsports reporter Chris Economaki had arranged a courtesy Renault for the weekend. After a quiet night in Paris, they figured out the French traffic nightmare well enough to drive the 120 miles down to Le Mans.

There, they found a different world.

———————————————————

This NASCAR-to-Le Mans project had been conceived six months earlier, during the 1976 Rolex 24 Hours in Daytona Beach. While there, officials from Le Mans approached NASCAR president Bill France Sr. about sending Winston Cup cars to their upcoming race. “Big Bill asked why Le Mans didn’t have a class for American stock cars,” NASCAR executive John Cooper recalled years later. “They said they’d create a class if we’d send over some cars. That’s how it all started, with casual conversation among people just standing around at a cocktail party on race weekend.”

Although ovals were its specialty, NASCAR had been racing on purpose-built road courses for years. At the time, Riverside in

California was an annual stop for its top series. Likewise, Watkins

Glen in New York had once been a regular stop. Stock cars had also raced on airport road courses at Linden, N.J. and Montgomery, Ala. And for several years, the famous Bridgehampton Circuit on Long Island, N.Y. hosted stock cars on NASCAR’s annual Northern Tour.

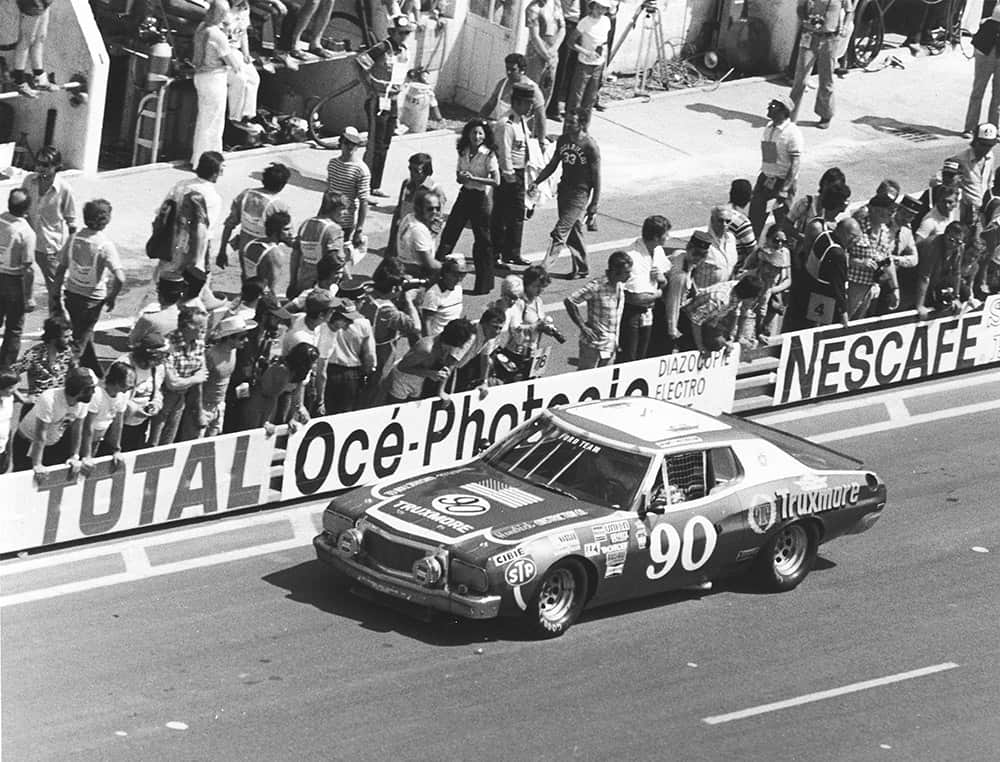

The offshoot of this agreement between NASCAR and the AOC was the two-car Grand International class. France and his staff asked Oregon owner/driver McGriff and son, Doug, to enter a No. 4 Dodge Charger. They also asked Donlavey to enter a No. 90 Ford for Richard Brooks and Dick Hutcherson, plus Frenchman Marcel Mignot, an instructor at the track’s driving school. The two stock cars had no chance of winning or

even finishing, but that wasn’t the point.

NASCAR simply being accepted on the grid and racing at Le Mans was the point.

—————————————————————

The historic trip would be expensive beyond either owner’s means: packing and shipping cars and equipment to France from Oregon and Virginia; trans-Atlantic round-trip travel for the drivers and crews; lodging and meals; Le Mans-specific equipment not found in any stock car garage. Understandably, NASCAR and the AOC covered all expenses for both teams.

At the time, NASCAR fans wondered why McGriff and Donlavey were invited rather than stock car royalty. In truth, drivers for front-runners like Petty Enterprises, Bud Moore Engineering, Junior Johnson and Associates, DiGard Racing, the Wood Brothers, and Team Penske didn’t want to miss the June 12-13 Cup weekend at Riverside. The annual championship was determined by points, and contending teams couldn’t afford to lose points to run an exhibition race far from home. (FYI: David Pearson beat Bobby Allison, Benny Parsons, Ray Elder, and Buddy Baker at Riverside that weekend).

Three of the four stock car drivers at Le Mans were fairly

accomplished road racers. (Only the relatively inexperienced

31-year-old Doug McGriff was in over his head). Hutcherson, a

long-time Ford loyalist, had been part of that company’s famous GT40 effort, finishing third at Le Mans in 1966. Brooks was a talented young Californian who had done well on NASCAR tracks of all shapes and sizes. And the elder McGriff had an impressive road course resume that stretched back almost a quarter-century.

“I’m guessing my road racing background is one of the reasons they chose our team,” McGriff said shortly after the race 47 years ago. “I’d won the Panamericana (Mexican Road Race) in 1950 when was I only 22. I’d won 14 stock car events at Riverside, and I’d run the 24 hours of Daytona. They knew I was capable on road courses and wasn’t just a circle-track guy.”

Still, having two big, hulking, lumbering Detroit products in a twice-around-the-clock road race was going to be tough. Still, having two big, hulking, lumbering Detroit products in a twice-around-the-clock road race was going to be tough.

————————————————————————

The first thing that came to Donlavey’s mind was perfectly

understandable: “Did he say Le Mans? Really? Le Mans, as in that race in France. Did he just ask if I wanted to take my team to Le Mans? Really?”

Yes, in fact, that was exactly what Cooper had asked when he called Donlavey in March of 1976. The NASCAR executive wanted owners willing to accept the ACO’s invitation to take their Cup cars to the upcoming 24-hour race. Donlavey had always gotten on well with the suits in Daytona Beach, mainly because he was a quiet, well-behaved, respectful Navy veteran who represented racing in a gentlemanly manner. Since nobody didn’t like “Chief,” Cooper felt comfortable the popular owner would mind his manners in Europe.

Like Donlavey on the East Coast, McGriff had always gotten along well with people in Daytona Beach. He and France Sr. had become friends after meeting as competitors at the 1950 Mexican Road Race. Impressed by the West Coast driver’s skill and dedication, France Sr. suggested he come to the Southeast to race stock cars. McGriff hesitated for a while, then responded by winning three Cup races in a six-week span late in 1954. By the time he went to Le Mans, he already had 41 starts on road courses. Officials were confident he’d represent stock car racing in the best possible light.

“It was a wonderful trip, a special and memorable time for my team,” Donlavey said in 1976, shortly after returning from France. “We saw things and did things we’d never seen or done; things we’ll probably never see or do again. Talk about feeling special! There we were, a bunch of little guys from a mostly-volunteer Virginia team running a Ford stock car against those Porsches and Ferraris and prototypes. Let me tell you… that was

the last place I ever expected to be racing.”

In truth, making the show wasn’t all that complicated. Because they were in their own two-car class, the Ford and Dodge were close to race-ready right off the boat. “We didn’t have to do much to the cars to make them legal,” McGriff, a recent NASCAR Hall of Fame inductee, told Auto Week magazine several years ago. “Windshield wipers, more headlights, taillights. You know, stuff we’d need if it rained or when it got dark. But nothing we would have needed in a Cup race back home. Mostly, they wanted us to put on bigger side mirrors so we’d see their little cars coming after us.”

As expected, neither stock car practiced or qualified very well. The McGriff Dodge was 47th on the 55-car grid and the Donlavey Ford was 54th. Even so, neither team was terribly upset since they were just happy to be making history.

—————————————————–

Meanwhile …..

Even without paperwork, Hallman and Pearce wrangled their way into the media parking lot on Friday afternoon. “We just kept driving into the lot and saying ‘journaliste’ to anyone who tried to stop us,” Hallman said. “NASCAR had arranged all-access media credentials, which made getting around the pits, paddock, and garages easy. Once we got our yellow armbands – which included a postage stamp-sized mugshot – we went to work. There was so much to see, so much to learn and understand. The whole thing was kind of overwhelming until we got the feel for things.”

They hung out all day Friday with the Donlavey and McGriff crews – McGriff kept several cases of iced-down Olympia beer handy – and learned that most Europeans had never seen anything like the racing Ford and Dodge. Hundreds of fans surrounded the cars during a parade and afterward, in the garage, paddock, and along pit road.

“Before we got there, they’d taken the cars all over France on a flat-bed truck (to advertise and promote the race),” said Donlavey, who died in 2014. “People didn’t know what to make of them, being so big and painted up and all. They called them ‘the two big monsters’ or something like that. They were the hit of the weekend.”

Perhaps appropriately, the international media nicknamed the cars “les deux monstres.” They were, after all, enormously oversized compared to the small, light, and nimble Porsches, Mirages, Lolas, Renaults, and BMWs ahead of them on the grid. The stock cars were curiosities from the moment they were unloaded and passed pre-race inspection … known in European racing as “scrutineering.” They were paraded through downtown Le Mans, where gawkers photographed them almost endlessly.

McGriff remembers how impressed fans were when the unmuffled V-8 engines unleashed their throaty growls. “For a week, in almost every paper, there was a picture of it,” he said of his Charger. “They loved it because it was big and loud and had a different engine roar. Too bad it didn’t run any longer than it did. We had built our engine anticipating 90- to 92-octane fuel, but what we got was 80- to 81.

“That’s why we only lasted a couple of laps before it blew up. Junie had a 351-inch, low-compression, short-track engine from Bud Moore, so the lower-octane fuel didn’t bother him. Our car would have been pretty good if we’d had different fuel.”

Alas, “pretty good” wouldn’t have been nearly good enough. While most of NASCAR’s attention was on the Cup race at Riverside that weekend, the Martini Porsche of Jacky Ickx and Gijs van Lennep was winning Le Mans by 11 laps after leading 349 of 354 laps, including the final 342.

————————————————————-

With nowhere to stay, Pearce and Hallman found space on the floor of the small cabin where some Donlavey crewmen were being housed. On Friday night, they happened upon a nearby bar that catered to race fans and team members. There, taped to a mirror behind the bar, was a newspaper photograph of the No. 90 Ford. In the background, quite by accident but clear as a bell, was Pearce’s smiling face.

A “well-refreshed” customer recognized him by the photo and incorrectly assumed he was a driver. Thinking they had an American celebrity in their midst, the patrons began plying Pearce and Hallman with all manner of French beer and wine. When hailed as “les pilotes,” the reporters said they weren’t drivers at all, but simply “journalistes.” Seconds after fans realized their mistake, the free drinks promptly dried up. It was, of course, fun while it lasted.

The “journalistes” were at the track all day Saturday, and stayed there from the race’s 3 p.m. start until the No. 90 Ford had terminal transmission problems around 2 a.m. Brooks was on the far side of the course at the time, unable to nurse the car back around for repairs. Even so, the Donlavey No. 90 entry had acquitted itself well by lasting 11 of the 24 hours and completing 104 laps, almost 890 miles, far longer than any American stock car race. They were scored 40th overall and 13th among

the 15 cars classified as “Did Not Finish.” The McGriff entry lasted

only two laps before dropping out with octane-related engine problems. It was scored 54th, next-to-last among the 55 starters.

Almost sleepless, Hallman and Pearce hustled back to Paris very early Sunday morning, returned the courtesy Renault, and managed to get to Charles De Gaulle Airport in time for their non-stop flight to Newark. They drove overnight back to Virginia and were at their desks – Hallman in Richmond, Pearce about 80 miles away in Newport News – in time to help put out their

newspaper’s afternoon edition.

To them, it wasn’t much different than driving overnight after a Cup race at Talladega to be at work Monday morning.

————————————————————

The 2022 announcement that NASCAR would enter this year’s June 10-11 race caught many series-watchers by surprise. It’s the 100th anniversary of the race, but only its 90th running. There was no race in 1936 due to a national workers’ strike, nor was there racing between 1940-1948. The area around Le Mans and the circuit itself had been badly damaged in World War II. Understandably, racing was not of great concern to the France people in the years immediately after the war.

With so much focus on the Next Gen car, it seemed unlikely that NASCAR would undertake another major challenge so quickly. Even while acknowledging the Hendrick Motorsports-prepared entry is primarily a publicity-seeking, market-driven “special project,” something as unprecedented as another Cup car at Le Mans is, truly, another big deal.

The American effort will be better prepared this time. Former championship-winning crew chief Chad Knaus has prepared a Chevrolet Camaro ZR-1 for the single-entry “Innovation Car” class. Team owner Rick Hendrick has recruited seven-time NASCAR champion Jimmie Johnson, plus 2009 Formula One champion Jenson Button, and noted road racer

Mike Rockenfeller to share the wheel. (Former Cup champions Kyle Larson and Chase Elliott of HMS will be at Sonoma for their own road race that weekend).

From a financial angle, corporate partners Chevrolet, Goodyear, and NASCAR will spend whatever it takes to make a good showing.

Since 2012, the AOC has reserved a grid spot for an entry testing new technology and innovation. The program, called Garage 56 (so named since only 55 teams are officially entered at Le Mans), offers an entryway for cars to be judged more for their design and innovation than the ability to be competitive. The Hendrick entry will be scored and classified as all other cars in the official results and “win” its one-entry class … for whatever that’s worth.

Hendrick, who will accompany his car to Le Mans, is optimistic: “We’re competitors and have every intention of putting a bold product on the track,” he said when the deal was announced last year. “It’s a humbling opportunity, but our team is ready. We’re not taking this lightly. This is a full-bore, full-blown effort to run 24 hours and to run competitive times. We’re not going over there to ride around. We’re going to put the best effort out there and run very competitively and finish the race. That’s a tall order (but) I feel strongly we can do it.”

Certainly, more so than 47 years ago, hope springs eternal.

Click for More Coverage of the 2023 24 Hours of Le Mans